The generally accepted idea by the scientific world is that Mars is a barren and lifeless place. But one researcher suggests that experiments by NASA’s Viking lander in 1976 may have accidentally killed microbes living in Martian rocks. Other experts are skeptical.

The generally accepted idea by the scientific world is that Mars is a barren and lifeless place. But one researcher suggests that experiments by NASA’s Viking lander in 1976 may have accidentally killed microbes living in Martian rocks. Other experts are skeptical.Did NASA kill life on Mars?

Recently, a scientist claimed that NASA may have accidentally discovered life on Mars almost 50 years ago and then accidentally killed it without realizing what happened. But other experts are split on whether the new claims are a forced fantasy or an intriguing possible explanation for some surprising experiments in the past.

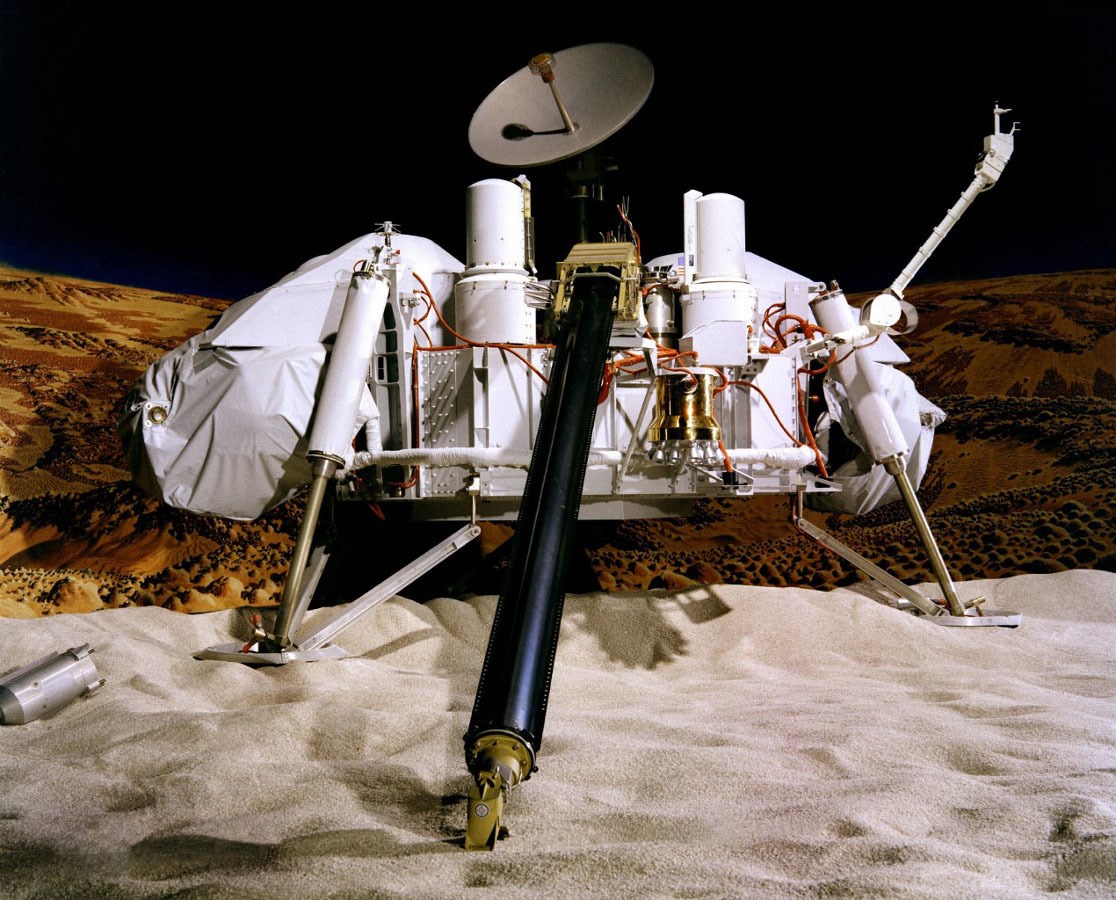

Dirk Schulze-Makuch, an astrobiologist at the Technical University of Berlin, wrote in a June 27 article for Big Think that NASA’s Viking probes may have sampled small, drought-tolerant life forms hiding in Martian rocks after landing on the Red Planet in 1976. suggested. Schulze-Makuch says that if these extreme life forms existed and continue to exist, they may have died from experiments carried out by the landing craft.

Schulze-Makuch added that this is “a suggestion that some people will certainly find provocative,” but that similar microbes live on Earth and could hypothetically live on the Red Planet, so they cannot be ignored.

Viking experiments

Each of the Viking landers (1975 – Viking 1 and Viking 2) conducted four experiments on Mars: the GCMS experiment, which looked for organic or carbon-containing compounds in Martian soil, the pyrolytic release experiment, which tested carbon fixation by potential photosynthetic organisms, and the radioactively traced nutrients added to the soil the labeled release experiment, which tests metabolism; and the gas exchange experiment, which tests the mechanism by monitoring how gases known to be key to life (such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen) change around isolated soil samples.

Each of the Viking landers (1975 – Viking 1 and Viking 2) conducted four experiments on Mars: the GCMS experiment, which looked for organic or carbon-containing compounds in Martian soil, the pyrolytic release experiment, which tested carbon fixation by potential photosynthetic organisms, and the radioactively traced nutrients added to the soil the labeled release experiment, which tests metabolism; and the gas exchange experiment, which tests the mechanism by monitoring how gases known to be key to life (such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, and nitrogen) change around isolated soil samples.While these were highly technical experiments, the results of their experiments were confusing and seem to continue to confuse some scientists ever since. Labeled emission and pyrolytic emission experiments produced some results that support the idea of life on Mars: In both experiments, small changes in the concentrations of some gases indicated the presence of some kind of organism.

GCMS also found traces of some chlorinated organic compounds, though mission scientists at the time believed these compounds were contamination from cleaning products used on Earth. (Next lander and reconnaissance instruments proved that these organic compounds occur naturally on Mars).

However, the gas exchange experiment, considered the most important of the four experiments, proved negative, leading most scientists to conclude that the Viking experiments did not ultimately detect Martian life.

Using water may have affected the experiments

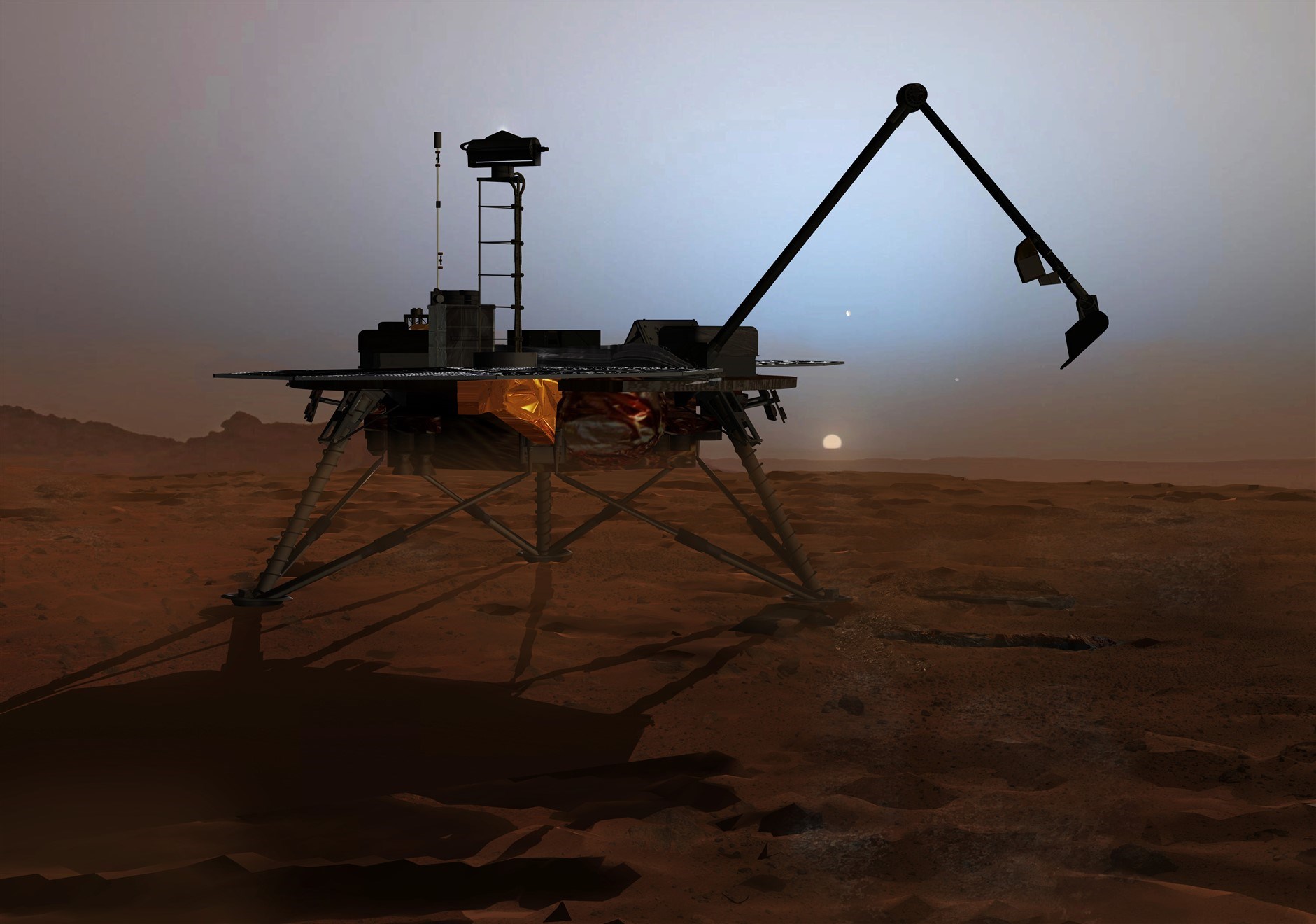

In 2007, NASA’s Phoenix rover, successor to the Viking rovers, found traces of perchlorate used in fireworks and explosives on Mars. However, the opinion that these traces were not sufficient for life on Mars was dominant. But Schulze-Makuch believes that many of the experiments may have produced skewed results because they used too much water. (Tagged release, pyrolytic release, and gas exchange experiments all involved adding water to the soil).

In 2007, NASA’s Phoenix rover, successor to the Viking rovers, found traces of perchlorate used in fireworks and explosives on Mars. However, the opinion that these traces were not sufficient for life on Mars was dominant. But Schulze-Makuch believes that many of the experiments may have produced skewed results because they used too much water. (Tagged release, pyrolytic release, and gas exchange experiments all involved adding water to the soil).In very dry Earth environments, such as the Atacama Desert in Chile, there are extreme microbes that can thrive by hiding in hygroscopic rocks that are extremely salty and draw very little water from the air around them. These rocks also exist on Mars, which hypothetically has a moisture level that could sustain such microbes. Schulze-Makuch suggests that if these microbes also contained hydrogen peroxide, a chemical compatible with some life forms on Earth, it would help them absorb more moisture and may also have produced some of the gases detected in the labeled release experiment.

But too much water can be deadly for these tiny organisms. In a 2018 study published in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers found that extreme flooding in the Atacama Desert killed up to 85 percent of native microbes that were unable to adapt to wetter conditions.

This is why adding water to potential microbes in Viking soil samples could be equivalent to stranding humans in the middle of an ocean: They both need water to survive, but at the wrong concentrations, it can be deadly to them, Schulze-Makuch notes.

There are other discussions

This isn’t the first time scientists have suggested that Viking experiments may have accidentally killed Martian microbes. In 2018, another group of researchers suggested that when soil samples were heated, an unexpected chemical reaction may have incinerated and killed microbes living in the samples. This group claims that this may also explain some of the surprising results from the experiments. Despite all this, the scientific community simply accepts these claims as “forced”.