Fried bread and toast derivatives are consumed frequently and fondly in many different regions of the world. However, although we love these breads that are baked for the second time, if they are burned, their taste becomes much worse and, according to general acceptance, it can cause cancer.

What is the Maillard reaction?

Like all cooking methods, frying is a type of chemical reaction. In fact, it is a very specific reaction and it is called the Maillard reaction. This reaction only occurs at temperatures around 120°C.

While the Maillard reaction is a fairly complex process when you break it down, it can be basically explained as follows: While other foods may have options such as lactose or ribose, reducing sugars, which for bread basically means maltose and glucose, react with the amino acids found in the bread, causing both a change in color and It also produces a lot of interesting taste and aroma molecules.

Essentially, the flavor of most cooked dishes comes about thanks to the Maillard reaction. “Hundreds of different flavor compounds are created in this process,” says Science of Cooking. “These compounds then break down to create more new flavor compounds, and so on.” “Each type of food has very different flavor compounds formed during the Maillard reaction.”

However, the problem here stems from these amino acids, especially amino acids called asparagine. In 2002, scientists in Sweden discovered that the Maillard reaction takes these asparagine amino acids, found in many favorite foods including potatoes, bread, cereals, cookies, and coffee, and produces a nasty little substance known as acrylamide.

Acrylamide, on the other hand, is an organic compound that is actually white, oddly enough considering it is formed when we toast toast. This substance is listed as “confirmed carcinogen” by the NIH National Library of Medicine and “highly toxic” by CAMEO Chemicals. When it’s not making our fries so delicious, it’s used in sewage and waste treatment, in paints and adhesives, and if that’s not enough, it can explode when exposed to too much heat or natural light.

Despite all this, it is not unusual to have it in your food. “Acrylamide is likely to have been present in food since cooking began,” says the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) fact sheet on the compound, adding: “It is almost impossible to completely eliminate acrylamide from the diet.”

Danger of acrylamide

Unfortunately, acrylamide is not very good for us. It is known to be neurotoxic, meaning it disrupts our nervous system, and long-term exposure through food can increase the risk of neurodegenerative disorders such as dementia. It can even cause problems in developing fetuses. “Acrylamide passes through all tissues, including the placenta, because it has a low molecular weight and is soluble in water,” says Federica Laguzzi, assistant professor of cardiovascular and nutritional epidemiology at the Karolinska Institutet Institute of Environmental Medicine in Sweden, in a conversation with BBC Future.

The worst part is that it increases the risk of cancer. Studies have conclusively shown that high levels of acrylamide cause cancer in animals. Epidemiological studies also indicate that the same situation may be valid for humans. The compound was linked to higher rates of breast cancer, kidney cancer, endometrial and ovarian cancer, and cancer in general.

However, as ridiculous as all this may sound, we cannot say for sure whether eating acrylamide is actually dangerous. There are some pretty big problems when it comes to measuring cancer risk in humans. “You need to do clinical trials to be able to say that it actually causes cancer,” said Rashmi Sinha, a senior researcher at the US National Cancer Institute, in an interview with Inverse. “But you can’t do clinical trials with things that are likely to be carcinogenic.”

Although laboratory studies have shown that acrylamide causes cancer, the FDA fact sheet on the substance states that “the levels used in these studies…were much higher than those found in human foods,” and these tests were conducted on mice and rats. However, it is unlikely that we will get such data in humans.

Instead, Sinha says, “the main studies were association [or] prospective studies” that relied on self-reporting over a long period of time. “We ask [healthy participants] questions about how they cook their food, and then we follow them for ten, fifteen, twenty years,” says Sinha. “[Then we] follow people with cancer to see if there’s anything about the way they cook food.” “We compare it to those without cancer.”

You may immediately notice some problems with this method. First of all, people can lie or at least distort the truth in any survey. Another problem is that we humans have really bad memories at remembering things. Therefore, it is possible that the information the researchers obtained was at least somewhat skewed.

Okay, but should we eat toast?

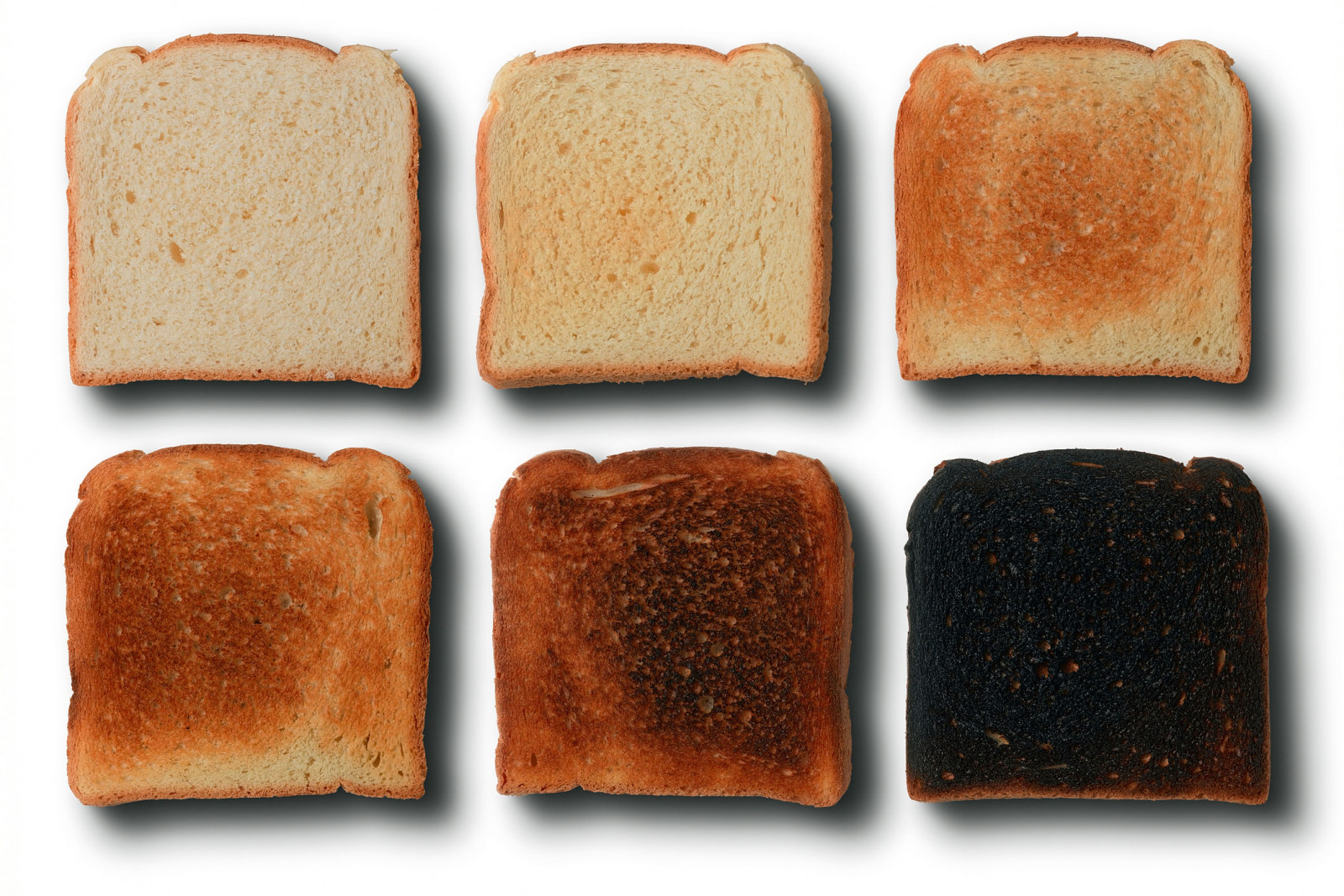

You are confused and still the most curious question is, “Can we still eat toast?” it could be. As always with human health questions, we can’t say for sure, but unless you’re toasting your bread to charcoal, you’ll probably be fine.

Not only is your exposure likely lower than it was 20 years ago, for example, thanks to campaigns adopted by both governments and individual companies, but our bodies may have built-in protective mechanisms against the compound, says Laguzzi: “We also don’t ingest acrylamide on its own. “This substance is found in foods that may also contain other components such as antioxidants that can help prevent toxic mechanisms.”

There are also very simple ways to reduce the level of acrylamide in your food. For example, when potatoes are kept in hot water for 10 minutes, acrylamide formation is reduced by nearly 90 percent.

The solution for toast and toast is equally simple and you just need to avoid burning the bread.